Authors Columns of the Day Sport Guest Life All Authors

Abdulhamid II's censorship

Abdulhamid II established a suffocating regime of despotism marked by secret police, denunciations, and exiles. One of the most critical pillars of this oppressive regime was press censorship.

AKP government shut down the social media platform Instagram. The 22 years of the political Islamist AKP government's oppressive regime, characterized by ever-increasing bans, evokes the "press censorship" that was the most important part of the oppressive regime of Abdülhamid II, the role model of the AKP government.

In the Ottoman Empire, shortly after the first newspapers began to be published in the 19th century, various legal measures were introduced to control the press.

The 1864 Press Law

The first press law in the Ottoman Empire was the "Matbuat Nizamnamesi" (Press Law), enacted in 1864 during the reign of Sultan Abdulaziz, adapted from the French Press Law. This law was not ostensibly a censorship regulation. However, under this law, publishing a newspaper required a licence that could be revoked at any time. The newly established Press Directorate oversaw newspapers before they were published. The Police and Gendarmerie Court would handle press-related crimes, and the Judicial Council had the authority to shut down newspapers temporarily or permanently. There was no right to appeal these decisions. Many newspapers were closed under this law.

The 1867 Ali Decree

The press bans in the 1864 Press Law, which would remain in effect until 1909, soon became insufficient for the Ottoman government. On March 16, 1867, the Ali Decree was issued, increasing the press restrictions. This law was seen as Grand Vizier Ali Pasha's attempt to silence the opposition press that criticized his misguided policies during the Cretan revolt.

Namık Kemal’s newspaper Ibret was shut down in 1873 after the staging of his play “Vatan Yahut Silistre.” Namık Kemal, Nuri Bey, Ebuzziya Tevfik, Hakkı Efendi, and Ahmet Mithat Efendi were arrested and later exiled. During this period, many newspapers and magazines, including Diyojen (the first Turkish satirical magazine), its successor Çıngıraklı Tatar , and Hayal , were either suspended or closed indefinitely.

On 12 May 1876, Grand Vizier Mahmut Nedim Pasha issued the first censorship decree, which remained in effect for a short time.

Abdulhamid’s Repressive Regime

When Abdulhamid II’s extreme suspicion combined with his fear of being dethroned and killed, his 33-year reign became a true "reign of fear."

His excessive suspicion and great fear led Abdulhamid II to exert tight control over his ministers, the military, students, the ulama, and the entire system.

During his reign, the state was ostensibly run by the Sublime Porte, but in reality, it was governed from the palace. Ministers were almost powerless. Ministerial appointments were often made without the ministers’ knowledge. Issues were discussed and resolved in the palace. Even foreign ambassadors would directly engage with the palace on important matters. Knowing this, ministers tried to curry favour with the palace to keep their positions. Appointments in the state bureaucracy were based on loyalty rather than merit.

Abdulhamid II chose those who were most loyal to him. He preferred individuals who could be easily bought with various ranks, medals, rewards, and hefty salaries. He would grant palaces, mansions, and estates to those who would be loyal to him. He would try to buy off his opponents by offering them money or positions. Those dangerous individuals whom he could not control or buy were generally exiled.

Abdulhamid’s reign of fear was shaped around four main concepts: secret police, denunciations, exile, and censorship.

Abdulhamid II’s suspicions and fears turned into an instinct to monitor and control everything and everyone. For this reason, he established a spy organisation. The first condition for gaining Abdulhamid II’s trust was to provide him with denunciations (both true and false rumours). This was known as jurnalism . The sultan would reward those who engaged in jurnalism and espionage with money and various gifts. He would even gift palaces, mansions, and estates to the leading jurnalists and spies.

Abdulhamid II skilfully eliminated his influential opponents. For example, Mithat Pasha and Mahmut Pasha were exiled to Taif after an unjust trial, where they were reportedly killed.

Bülent Tanör describes Abdulhamid’s repressive regime: "Until the Second Constitutional Era (1908), the Ottoman Empire was ruled under Abdulhamid’s oppressive and dark regime. Leading constitutionalists like Midhat Pasha were sidelined, exiled from the capital, or bought off. Personal security and freedom were completely eradicated, and a ‘state of fear’ was established with a network of spies and denunciations. As expected, all state powers were concentrated in the sultan’s hands during this period. The grand vizier and ministers were reduced to mere administrators." (Tanör, p. 21)

One of the most critical pillars of Abdulhamid II’s stifling regime of despotism was press censorship.

Abdulhamid II’s Press Censorship

According to Article 12 of the 1876 Constitution, “The press is free within the bounds of the law.” During this period, various regulations were introduced to make press laws as stringent as possible.

The first example of press censorship during Abdulhamid II’s reign occurred when Teodor Kasap was sentenced to three years in prison for a cartoon in his satirical magazine Hayal that referenced Article 12 of the Constitution. The Decree on Martial Law issued on 2 October 1877 granted the government the authority to suspend or even shut down newspapers whenever necessary. Thus, Abdulhamid II established a legal basis for his censorship.

On 1 March 1878, a censorship committee was established by one of Abdulhamid II’s loyal men and placed under the Press Directorate. Newspapers were reviewed by the censorship committee at the Press Directorate before publication. Censored sections of newspapers were left blank.

On 22 January 1888, a new Printing Press Regulation was enacted. This law covered printers, booksellers, type foundries, and publishers of books and periodicals. It prohibited the publication of any work without the approval of the Ministry of Education.

In 1888 and 1894, further regulations institutionalised Abdulhamid II’s press censorship.

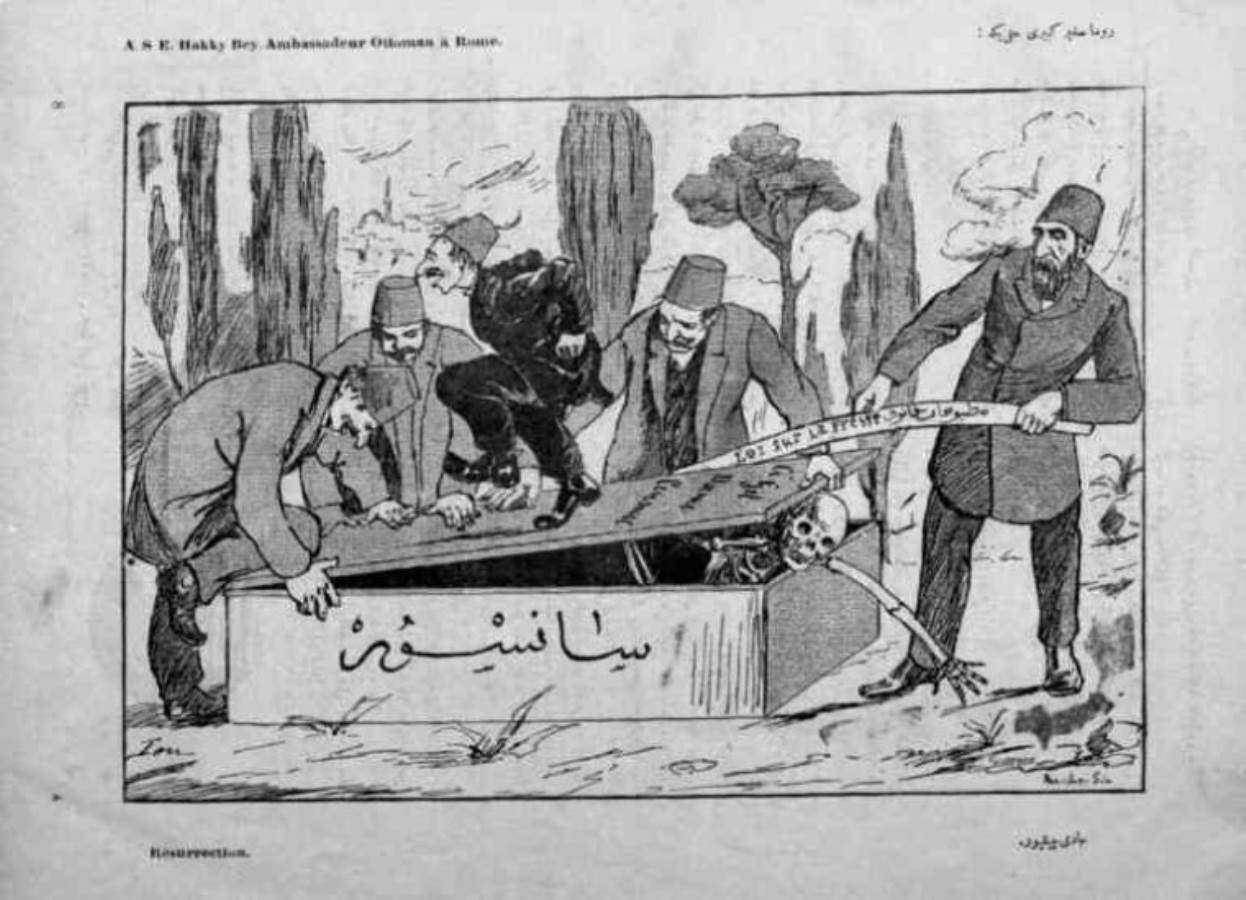

In a cartoon, the specter of censorship is seen rising from its coffin. Next to the opened coffin is the word “censorship,” and on the crowbar held by Sultan Abdulhamid II is written “Press Law.” Kalem , Issue: 24, 6 February 1909.

According to a nine-article secret directive dated 1888:

1. The press had to prioritise reporting on the good health of the ruler, the increase in agricultural yields, and the development of trade and industry in Turkiye.

2. No serialised fiction not approved by the Minister of Education and the Morality Commission was to be published.

3. Newspapers were not to publish long literary or scientific articles, nor use the phrases “to be continued” or “continued tomorrow.”

4. There were to be no blank white spaces, dots, or dashes in any article, as such could lead to erroneous assumptions and confusion.

5. Newspapers were not to publish accusations of crimes; theft, embezzlement, or murder involving state officials.

6. The publication of petitions complaining about the poor management of responsible state officials was prohibited.

7. The use of all historical and geographical names, particularly the term “Armenia,” was banned.

8. Newspapers were prohibited from publishing news about assassination attempts on foreign rulers or any reports of uprisings in foreign countries, regardless of the circumstances.

9. These new rules were not to be published in the newspaper columns, as they could provoke criticism. (Ataman, pp. 42-43)

Abdulhamid II allocated monthly stipends to newspapers to control the press. The amount depended on the newspaper owners’ loyalty to the palace. Writers who penned laudatory articles about the palace were rewarded with ranks and medals. During Ramadan, journalists visiting the palace were given "teeth rent" according to their importance. Abdulhamid II also gave gifts and favours to foreign press that he wished to influence.

A large number of words that bothered Abdulhamid II were banned. For example, the words "star," "madness," "constitution," "revolution," "anarchy," "anarchist," "strike," "dynamo," "dynamite," "bomb," "freedom," "equality," "brotherhood," "homeland," "nation," "oppression," "socialism," "international," "republic," "senate," "parliament," "continent," "explosion," "heir apparent," "ill," "Mithat Pasha," "Sultan Murat," and "Namık Kemal" were banned, and according to witnesses of the time, even words like "nose" and "behind" were banned because they were thought to evoke Abdulhamid’s nose and the island of Crete, respectively. Mentioning balloons and airplanes was also frowned upon.

Abdulhamid II’s press censorship was full of tragicomic incidents. For example, the magazine Servet-i Fünun wanted to publish a picture of an old man praying at a fountain in one of its issues. The Press Director did not grant permission, arguing that it could be interpreted as saying, "Our fate is now in the hands of prayer!" When İsmail Safa wrote, "Will spring not come? / Will spring not come?" in Saadet newspaper, the censorship board was furious.

During the reign of Abdulhamid II, newspapers feared writing about the opening of parliament in Russia, and about the declaration of the constitution in Iran. They also avoided reporting on assassinations of foreign monarchs.

To prevent the palace's political failures from becoming public, discussing Egypt, Sudan, Tripolitania, Crete, Yemen, Armenia, and Bulgaria was forbidden.

Not only newspapers but also magazines and books were censored. Various committees were established for this purpose, particularly targeting history books. The Sultan feared history so much that certain historical subjects were banned in some classes.

Mail from abroad was strictly monitored. Customs officials could tear out any page from a book. One ignorant censor equated the word "dynamic" in a European "Thermodynamics" book with "dynamite" and banned its entry into the country.

In 1902, many banned books were burned at the Çemberlitaş Hamam. Although no official list of banned words has been found, some lists of burned and banned books and newspapers are known.

In 1902, the State Printing House, Matbaayı Amire, was closed. The state printing house remained shut for six years until the declaration of the Second Constitutional Era.

Due to censorship and repression, many intellectuals and journalists fled abroad. The Young Turk press emerged in Europe.

Abdulhamid II disliked opposition journalists and intellectuals, especially the New Ottoman intellectuals Ziya Pasha and Namık Kemal. He appointed Ziya Pasha as the governor of Syria to keep him away from Istanbul. Namık Kemal was arrested on a report and, despite being acquitted, was forced to reside in Crete, later choosing Mytilene. He was made governor of Mytilene 2.5 years later, then Rhodes, and finally Chios, keeping him far from the capital.

During Abdulhamid II's reign, newspapers and magazines were shut down on flimsy pretexts, and their owners were punished.

Abdulhamid II's censorship particularly hindered political and social debates in the Ottoman Empire. This negatively impacted the development of national consciousness that began with the New Ottomans. In an environment where political discussions were banned, scientific, technical, and literary publications flourished.

It seems that the AKP government, modeling itself after Abdulhamid II, follows his example in censorship and repression. However, history shows that no regime of oppression lasts forever.

Bibliography

Bora Ataman, “Türkiye’de İlk Basın Yasakları ve Abdülhamit Sansürü”, Marmara İletişim Dergisi, C.14, S.14, 2014, s. 21-49.

Bülent Tanör, “Anayasal Gelişmelere Toplu Bir Bakış.” Tanzimat’tan Cumhuriyet’e Türkiye Ansiklopedisi, C. 1, 1985, s. 10–26.

Cevdet Kudret, Abdülhamit Döneminde Sansür, 2.C. İstanbul, 1977.

Fatmagül Demirel, II. Abdülhamid Döneminde Sansür, İstanbul, 2007.

Hıfzı Topuz, II. Mahmut’tan Holdinglere Türk Basın Tarihi, İstanbul, 2003.

İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı, Mithat Paşa ve Taif Mahkûmları, Ankara, 1992.

Orhan Koloğlu, Abdülhamit Gerçeği, İstanbul, 1987.

Süleyman Kani İrtem, Abdülhamit Döneminde Hafiyelik ve Sansür, İstanbul, 1999.

Yusuf Hikmet Bayur, Türk İnkılabı Tarihi, C.1, K.2, Ankara, 1964.