History's longest pandemic lasted a full '15 million years'

Imagine discovering a pandemic that didn't last for a couple of years, but for a staggering 15 million years, affecting our ancient mammalian relatives ranging from the early primates to creatures as diverse as aardvarks and pandas.

This is not the plot of a science fiction novel but the story of ERV-Fc, a prehistoric viral saga that still whispers secrets in the DNA of modern mammals, including humans.

Between the distant epochs of 33 million to 15 million years ago, during a time known as the Oligocene to the Early Miocene, ERV-Fc embarked on a viral conquest across the globe.

It didn't just infect hosts; it made its genetic mark on them, a legacy that has quietly endured through the ages. Interestingly, up to 8% of the human genome consists of remnants from these ancient invaders, showcasing the profound and lasting impact these prehistoric viruses had on mammalian evolution.

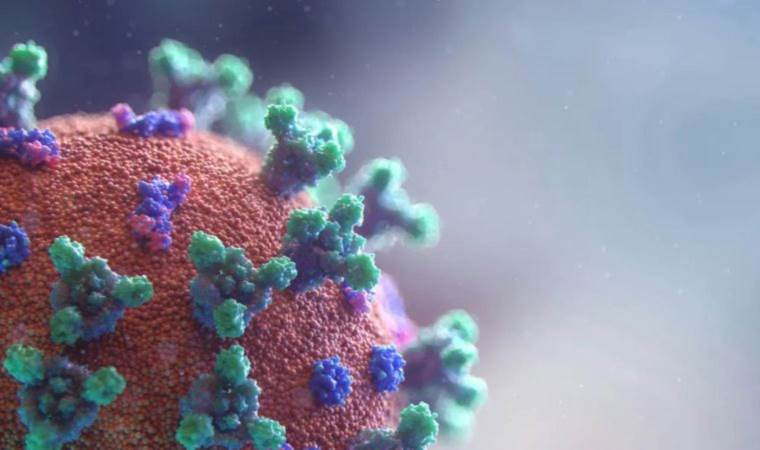

The way these ancient viruses operate is quite fascinating. Similar to how modern retroviruses like HIV work, they integrated their genetic material into the DNA of their hosts.

However, for their legacy to last millions of years, these viruses had to invade germ cells—the very cells responsible for passing on genes from one generation to the next. Once embedded in the genome of germ cells, these viral sequences could be inherited by future generations, becoming a permanent part of the host's genetic makeup, a phenomenon known as an endogenous retrovirus.

ERV-Fc stands out as a testament to the viral world's tenacity and adaptability. In a groundbreaking 2016 study, researchers found evidence of ERV-Fc's genetic remnants in 28 different modern mammals. This wasn't a simple case of a virus infecting a single lineage; ERV-Fc crisscrossed between species, causing an intercontinental pandemic that touched nearly every corner of the planet, except for the isolated terrains of Australia and Antarctica.

Today, ERV-Fc might not pose a threat to human health, its genetic remnants lying dormant within our DNA. Yet, understanding it and other human endogenous retroviruses could offer invaluable insights into our evolutionary past and present. It could even help us predict how contemporary viruses like HIV might influence the course of human health millions of years into the future.

"Mammalian genomes are like vast archaeological sites, housing hundreds of thousands of ancient viral fossils akin to ERV-Fc," said William E. Diehl, the lead author of the study.

He envisions using these ancient sequences as a lens to view the past, aiding in the prediction of future viral impacts and understanding the evolutionary interplay between viruses and their hosts.

In unraveling the mysteries of ERV-Fc, scientists are not just piecing together the story of a long-extinct virus; they're unlocking the secrets of our own genetic heritage and the intricate dance between life and the viral world that shapes it.